17 June 2010

The Final Days

After a night of celebrating and a late morning recovering from the vicious combination of sleep deprivation and drinking, I return to school Friday morning more out of habit than necessity. The third-year studio's reviews are on the last day or two of the semester so almost all the other students have left the city for summer internships and travel. (I haven't found a job yet, but I will be traveling to Costa Rica for a week after graduation and then I am moving to New York City.) The building is eerily vacant and quiet. Our studio's work is still pinned up in the lower gallery. Old coffee and cookie trays sit just as we left them the afternoon before as if awaiting another jury. Adding to the strangeness of the moment, as I start to take pictures to document our presentation, without a word a group of Asian film makers appear and start to document me. The cameraman crouches over me as I lean in to get a well-angled shot of our model.

I feel like a survivor documenting a catastrophic event. On my way up to the third floor I walk through the second year studio. It seems to confirm some calamity; models, acrylic, paper and cardboard strewn across the desks and floor. The trash cans are overflowing. Climbing to the third floor, I finally find signs of life.

I see my friend Adam who volunteers to help me move out of studio in his car, I accept, but with more than a week left before graduation, I can't quite bring myself to move everything home so soon. I like my graduate student life and I'm not quite ready to accept that school is over. Leaving my desktop computer behind gives me an excuse to come back at least one more time.

I pass the week playing tennis and meeting up with friends each night for various events--a raucous night of karaoke, burgers and beer, or a house party with dancing and ping pong. The following Friday--the deadline for students to get their stuff out of the building-- I return to Meyerson Hall to retrieve my computer.

As I pack, the studio passes through my mind--it was better than I had hoped. Balmond and Snooks' dedication to, and curiosity in, the non-linear design process had taught me if not to completely believe in it, at least to continue to explore atypical possibilities for architecture even as I start to work with the constraints of clients, budgets and city regulations. And even though our team had a strained relationship and a less than stellar final review, a round of handshakes after the critique confirmed that we are all still friends. Further, Balmond's encouraging words following the jury will inspire me for some time.

With the computer in hand, and another car-owning friend waiting at the back door, I finally leave the building.

20 May 2010

The Final Review

Architecture reviews start notoriously late, but Roland gave the studio strict instructions to be ready at ten o’clock in the morning because we have a tight schedule and an impatient jury. It is 9:40, and Dwight and I can’t get in touch with So. When I left the studio four hours earlier, we agreed to meet at 9:00 am to pinup our drawings and set up the model. I ask a friend to track So down while I drag our hundred-pound wood model down to the room where we are presenting. Dwight is still upstairs finalizing the digital presentation. Ten minutes later, Dwight has finished exporting the presentation and we are pinning up our two boards. I get a text from So—“Sorry, In a cab, will be there in five.” But before So shows up, Roland asks us to start because the group that was suppose to go first isn’t ready.

As Roland is introducing the jury, So rushes in visibly upset and apologetic. We settle him down enough to run through the presentation and discuss our speaking order before Roland announces “With that I will turn it over to the first group.” We introduce ourselves and I start. Unlike the mid-review, this time we have the presentation in the right order with the process before the result. We get to the first video, and the student changing the slides for us plays the video while I discuss the movement of the dots. I ask him to play the video again but instead he flips to the next slide. When we ask him to go back he misunderstands and advances another slide forward. The jury looks annoyed as So runs back to the projector. We move on hoping to get the jury’s attention. Dwight explains the sticks and their aggregation and alignment to physically define the spaces. As we show some renderings of the interior and exterior spaces, So uses the wood model to explain how we intend to physically connect the sticks together and eventually make them into a building. Satisfied with our presentation we await the jury’s reaction.

Perhaps a little overconfident with our work, (Cecil and Roland have been consistently pleased with our project and progress,) I am surprised by the first comment from one of my previous professors Jenny Sabin:

“Would you clarify some of the conditions that take place with this construction system? How do you distinguish structure, partition or floors and windows?”

Tom Wiscombe of Emergent Architecture says that he likes the effect of the building, the order of the interior compared to the fluffiness of the outside, but do we really think this system is organizing space in a way that creates a functional school of design. I reply that the while the spaces may not be organized in a traditional fashion, they are accurately sized to the numbers of people who would be using them, and the variation in spaces in the building would accommodate all of the programmatic needs of a school of design. He seems unconvinced and continues. He says that our design appears much more like a pavilion than a true building. “Do you really have any structure or enclosure?”

Balmond steps in to redirect the conversation in a more theoretical direction. He dismisses the structural concerns citing the wood model and the redundancy of the system, and then suggests that because of the redundancy, the users could actually move the sticks around and change the interior spaces as needed. Balmond’s ability to think realistically and conceptually at the same time, I believe, is the secret to his success as an engineer and designer. As the review wraps up, the conclusion of the jury is that our stick organization is successful, provocative, and beautiful, but most of the members still seem skeptical that the dots will really form spaces in the building.

I listen to the other reviews with some interest, but mostly I am just relieved to be done. As the jurors depart, Cecil approaches Jim and me, and in his typically blunt fashion says “I think there were two interesting projects this semester…well done.”

19 May 2010

Stickin' to It

Although the members of our team fundamentally disagree about how to write the algorithm and the desired result, after some heated discussion we resolve to continue to work together in the interest of finishing the project. One intention that we all agree on is to be the first project in Balmond’s studio to move from a theoretical idea to an actual construction system. With a large scale wood wall-section model, we will show how our building can actually be built.

Otherwise, we compromise, keeping the building messier on the exterior, with more random unaligned sticks, while on the interior they will align more closely into parallel rows and functional interior partitions. Once constructed, In order to create flat floors for the interior spaces, the densely packed sticks will be cut to the same height like freshly mowed grass. Windows in our building will be made of translucent sticks incorporated with the wood ones of the same size. Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Headquarters, our building won’t have views out of the building, but will still allow natural light into the interior.

With a compromise reached, but just five days left, we have a lot of work to do before the final review. Dwight works on the plans and sections in studio, while So and I haul the 6 30-pound boards for the model upstairs to the fabrication lab and start planing, joining, and cutting them into sticks.

05 May 2010

Towards a Final Review

After the trip to London and a brief stop in Barcelona we are back in Philadelphia and Balmond meets with us to see what progress we have made since the review. "At some point pragmatics kick in and you have to go with it" he tells us. He advises us that the script can't design everything and we need to take the results and find practical ways of meeting the real world requirements of a building.

Balmond's advice is something that deep-down we know, but we hate to hear. Up to this point we have been optimistic about the non-linear process and we believe that through scripting we can design every part of the building. Having Balmond tell us that we can't script the whole process is like the moment as a child when you realize that your parents aren't superheroes. While So and I do want to have a building generated from the project by the end of the semester, we want to push the scripting absolutely as far as possible before we switch to traditional design methods.

We are focused on how we can get the script into a full building form with floors and windows by the final review. The sticks are now aligning into a beautiful and credible building form on the site; the exterior looks something like hair spiraling around the crown of a head. We have even worked out a construction system for the thousands of 4 by 4 inch by six-foot boards required to build it. But fitting glass between the sticks requires something far less standardized than an off-the-shelf glazing system and we can't get the script to form flat floors.

Dwight has been pushing So and I toward the pragmatic for weeks now and we have fervently resisted. We haven't reached the point of divorce, but there is definitely some tension in the group. For So and I, Balmond's advice is a difficult pill to swallow.

27 April 2010

Sticky Review

We are six slides into our presentation and the jury is staring blankly at the

screen. In a last minute disagreement

Dwight, So, and I reorder our presentation to show a hypothetical building section before the process. The jurors

who have never seen our project before don't have any idea how we designed the

building and wall sections we are showing them.

I fidget nervously as Dwight introduces the project. Slide eight, a video of the groups of dots forming,

seems to awaken the jury. As it plays I fumble through a few sentences

about the formation of groups by the "professor" and

"student" dots (After seven

years of architecture school, I still haven't mastered verbal presentations.) So

explains the algorithm for the stick creation and movement: When a randomly moving particle touches the

boundary of a group it forms a line. Depending

on its neighbors, the new line adjusts

its length and orientation and is then extruded into a 3D stick.

"How do you simplify this to get more out of the algorithm?" Balmond asks. He is interested in the arrangement of the sticks, and how they could start to construct real walls. Our project is the first to address the materiality of architecture and they want us to take the sticks as far as possible. One by one, the rest of the jury also expresses their interest in the sticks. Rob Stuart-Smith like them so much that he suggests we get rid of the group algorithm completely and focus on the one idea. Removing the people doesn't thrill me at all and luckily Roland sides with me. He believes that with more differentiation based on size or designated activity, the groups can directly inform the stick alignment and the aesthetic of the building. Daniel Bosia, who with Cecil runs the AGU and was one of the first people to apply non-linear design to architecture ends our review excitedly: "picture millions of these little wooden sticks stacked and aligned into a building. " Relieved, Dwight, So and I nod in agreement.

The jury reviews three other projects without interruption. The third and fourth projects have a mixed reception, while the last receives high praise for the complexity of the code. As is typical with architectural reviews, the jury closes with a round of general comments and encouragement--advising that we should continue to tweak our algorithms while working toward a constructible design. On our way out, Bosia stops Dwight, So, and I and once again complementing our work, he asks if we would be willing to do a short presentation for the whole AGU in the morning. We gratefully accept.

Rendered images of the aggregation are

followed by videos on slides fourteen and fifteen of the sticks aligning and

stacking much like bricks to form walls. The jury finally seems interested as they watch the lines pivot back and forth adjusting their relationships.

"How do you simplify this to get more out of the algorithm?" Balmond asks. He is interested in the arrangement of the sticks, and how they could start to construct real walls. Our project is the first to address the materiality of architecture and they want us to take the sticks as far as possible. One by one, the rest of the jury also expresses their interest in the sticks. Rob Stuart-Smith like them so much that he suggests we get rid of the group algorithm completely and focus on the one idea. Removing the people doesn't thrill me at all and luckily Roland sides with me. He believes that with more differentiation based on size or designated activity, the groups can directly inform the stick alignment and the aesthetic of the building. Daniel Bosia, who with Cecil runs the AGU and was one of the first people to apply non-linear design to architecture ends our review excitedly: "picture millions of these little wooden sticks stacked and aligned into a building. " Relieved, Dwight, So and I nod in agreement.

The jury reviews three other projects without interruption. The third and fourth projects have a mixed reception, while the last receives high praise for the complexity of the code. As is typical with architectural reviews, the jury closes with a round of general comments and encouragement--advising that we should continue to tweak our algorithms while working toward a constructible design. On our way out, Bosia stops Dwight, So, and I and once again complementing our work, he asks if we would be willing to do a short presentation for the whole AGU in the morning. We gratefully accept.

21 April 2010

Time to Review

Walking up Cresent Street to Balmond’s offices on Tuesday morning, the anticipation is high. Finding the building, located on a dead-end side-street, turns out to be quite difficult and only adds to the tension. Once inside, Balmond’s personal assistant escorts us to a plain room on the ground floor where salmon sandwiches and sparkling water await us. She encourages us to set up our laptops and prepare for the review. Having only seen Balmond in our studio where he whisks in and out, his office seems like the lair of some mystical creature.

At two, Dwight saves our final PDF,(there are no drawings for this review, everything is digital,) and we are escorted to the Advanced Geometry Unit’s floor. There, surrounded by models of buildings we recognize--OMA’s Seattle Public Library and CCTV building in China, and Toyo Ito’s Serpentine Pavilion, the review begins. Education by architectural review is unique. Few other fields determine the success or failure of a student's work by a subjective and informal critique. Surrounded by a hum of activity, like athletes performing for Olympic judges, each student or group of student’s takes their turn. Andrew Saint, author of Architect and Engineer, describes the scene:

[The jury is] that day-long blend of ritual and endurance-test that is the central act of the studio-teaching calendar. Students pin up their work or set out their fragile models, dally, listen, disappear for a while, look in again, and finally, often falteringly, one by one present their ideas. Teachers and visiting critics fidget or frown, according to their lights, before giving vent to shrewd or arbitrary utterances. Between, there are long pauses. Everything runs late and seldom in the right order. Tension is high and exhaustion great, because many students have been up all night finishing their work. The crit can be formative, devastating, illuminating, initiating, alienating or just plain boring. In terms of the engineers, as a means of conveying skills or facts, it is neither systematic nor rational. Rather, it is an exercise in rhetoric for a calling that must be groomed to persuade.

Roland introduces the jury. Besides Balmond, the jurors include Roland’s partner, Rob Stuart-Smith, Daniel Bosia and Peter Jeffries from the AGU. The first team presents an algorithm that organizes the movement of people through space. Similarly to our team, this group has written an algorithm to generate one architectural element, in their case the circulation, and use that to control the design of the other parts of the building. A mesh enclosing the circulation will define the shell of the building. Then they will use a vine-like structural system to hold the two parts together. The presentation drags on—rather than the suggested ten minutes, the group talks for half an hour.

The jury listens patiently, asks questions and discusses. While this team's code for the circulation is quite complex and beautiful, (they have a former computer science major on their team,) the jury finds that the work lacks cohesiveness. Daniel Bosia states that the vines are lacking the number of points necessary to generate a believable structure. After watching a video three times of the meshing system wrapping the circulation paths, the jury seems uncertain what to make of it. Conceptually they like the project, but are unconvinced at this point that the elements can come together to make a building. As the discussion wanes Roland looks back to me and announces “You guys are next.”

13 April 2010

London Times

At eight in the morning on

Saturday, our studio of fourteen lands at Heathrow—tired and hungry from seven

hours on the plane, but excited about visiting the city and the offices of the

Advanced Geometry Unit. Business class

must make the trip much more tolerable, otherwise, I’m not sure how Cecil

Balmond could stand the trans-Atlantic flight every two weeks or more. It takes us three and half hours to get from the

airport to Paddington Station, then via the Underground to Tottenham Court

Road. Heading up the long, steep escalator to the street, I start to

recognize the place.

We

are near the Architectural Association, one of the best known schools of

architecture in the world where architects such as Zaha Hadid, and Rem Koolhaas

studied in the 1970s. I attended a three-week

summer program at the AA in 2006 and used this Underground stop almost every

day. My interest in non-linear design was first

piqued by a presentation that summer by architects Ben Aranda and Chris Lasch.

Fond

memories of my friends from the program fill my head as we walk past the AA

buildings in Bedford Square and finally reach the Langland Hotel. We drop off our bags in the luggage room and

with me leading the way head out for a proper English breakfast: greasy sausages, runny eggs, and the always

strange baked beans. We attempt to visit

the nearby British Museum to see Norman Foster's roof addition, but the jetlag

overwhelms us and we retreat to the hotel for a nap.

Four small twin beds—two separate

and two joined by full size sheets await myself and three roommates in our

converted attic. The toilet and the

shower are down the hall. It is not

luxurious, but for twenty pounds per person with an English breakfast included we

are happy to deal with our penthouse suite: Some of the other students disagree

and move down the street to roomier accommodations.

After our extended nap some of us

head out toward Trafalgar Square, determined to see the city despite Tuesday’s

looming review. Though I had been to

many of the buildings before, I see

Lloyd's of London for the first time and am shocked to find that Richard

Rogers' "high-tech" structure is concrete. We also see the Tate Modern Museum the Millennium

Bridge, and Big Ben before finding a pub for fish and chips and another strange

English side--mashed peas.

07 April 2010

Building Towards a Building

"Like the standing wave in front of a rock in a fast-moving stream," John Holland, a pioneer in non-linear science writes, "a city is a pattern in time." The analogy captures the emergence of organization that my team desires in our building. Rather than a city, we are designing a school of design. The rules, like the rock in the stream, constrain the pink and blue dots to form green groups. And now that the dots are moving around according to the rules, we can start looking for the waves.

After a week of adjusting the rules, we are not making waves. Dwight and So are losing faith in the process. At the beginning of the semester Balmond told us to “Be careful to reevaluate assumptions.” Now I know why. Roland still believes in my algorithm’s potential, but suggests that we add additional rules so that groups of dots form clearer organizational patterns. Initially many locations are equally viable, but just as people make a path through a woods by the repetition of use, we hope to designate rooms and their function by repetition.

Dwight and So are working on the walls and structure. They have reduced a process called a diffused limited aggregation--the process by which coral reefs are formed--down to just an aggregation. Much like dust or snow, in our process, points move around randomly and collect around any object or group. Rather than forming just an enclosure for the whole building, we want this aggregation process to make the walls and floors. The aggregation collects around the group spaces to create walls, and as they develop they limit the movement of the students and faculty. The two systems will interact until eventually they reach a point of stasis.

Will they really reach that point? I don't know, but I know that during his last visit Balmond insisted that we have renderings and drawings resembling a portion of the building for the mid-term review. We have a lot to do before Friday when we will fly to London to present to members of the AGU(Advanced Geometry Unit,) Cecil Balmond’s team of engineers, architects, mathematicians and programmers for our mid-term review .

27 March 2010

Dot Processing

Dwight, So and I start to sort out our ideas into a building. During our presentations earlier in the day, Balmond discourages So and others who were studying a grid-based system from continuing in that direction. The grid, he believes is too restrictive to allow interesting results. So prior to our next meeting with Balmond, we agree to use mine and Dwight's ideas to move forward with the building design. First we will use the space organization I developed to lay out the spaces of the building. Then we will use Dwight's system for building enclosure to create the exterior walls and windows. In the meeting Balmond confirms that there is potential in our process so we start on the algorithms.

The non-linear design process uses algorithms, or repetitive patterns to create forms. Knitting is an example of an algorithm. The repetition of pulling one loop of yarn through another and changing direction at a regular interval produces material. Unlike knitting, which uses an algorithm with known results, the results of our algorithms are unpredictable and variant. But with the right adjustment of the rules and their variables, the algorithms will create a design that can be built. The computer enables us to quickly test the algorithms and adjust the variables to get different results. The catch to this is translating the algorithms into commands that a computer can understand.

Writing computer code is not typically part of an architectural design studio, and often does not come naturally to architects. A few students have computer science backgrounds and can write lines of computer code as easily as English sentences, but the exactness of the process leaves the more creative and less logical architectural minds befuddled. I find myself somewhere in the middle--I have experience with scripting from an elective I took last semester, but I am not nearly as fast as some.

I write and edit code for a week attempting to get dots (representing the architecture students and faculty,) to behave the way I want. At first I can't get them to interact at all, then I can't get them to separate. On Monday Roland Snooks' advises me to switch to a program called Processing which can work through algorithms much more efficiently. As he predicts, by Wednesday's studio meeting, I have hundreds of red and blue dots wandering around the screen forming into groups. These groups, I hope, can start to layout the rooms inside Dwight's enclosure.

In the video blue dots represent students, pink dots are faculty and green dots are temporarily established groups.

23 March 2010

Team Building

We are required to work in teams of three, but forming these groups is not as easy as counting off. Studio groups involve friendship, working style, expectations, and language barriers. They are like short term marriages and you don’t want to end up divorced. Occasionally, in a studio, a break up happens leaving one person to do the work of three. And since, for the first three weeks we have already been individually brainstorming and researching ideas for non-linear architecture projects, compatibility of ideas was critical too.

The assignment for our studio is a new design school for Penn. I've been thinking about how people organize themselves into groups within a school of design. My initial assumption is that the functions of a building can be organized by simple rules based on desire of the students and faculty to learn. The process has the potential to define the proximity and size of rooms, but does little in terms of structure that could make a building. Knowing my limitations, I teamed up with Dwight Engel, a friend who has similar interests but I have never worked with before. For this studio he is interested in the relationship of structure and transparent surfaces--walls and windows.

So Sugita is an easy choice for a second teammate. Working together last semester we produced one of my favorite projects I have completed at Penn. Dependable and intelligent, he kept our group moving forward toward a final result. His interest in self-organizing circulation paths fit nicely with my programmatic spaces and Dwight’s structural ideas.

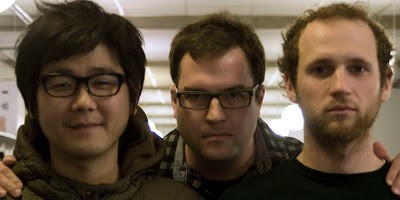

With the engagement confirmed, we meet--Dwight, a fit, stylish guy with curly brown hair who is always willing to talk about architecture; So, an immaculately dressed Japanese with black rimmed " architect" glasses; And myself, the least well dressed and the most opinionated of the group. We make our first decision, unanimously, to go out for burgers and beer.

Directed by Cecil B.

The NAAB has approved the architecture program at Penn with high praise, citing only safety and accessibility (the lack of handrails and handicap ramps in our drawings,) as a "student performance criteria" in need of improvement . With our degree assured, we can now get back to work preparing for our first meeting with Cecil Balmond.

After three weeks of working on diagrams and reading, biweekly discussions with Roland Snooks our assistant professor, and one false alarm--last week Balmond's flight was cancelled at the last minute-- he finally arrived.

At four o’clock two men in black walked in to the studio. The black attire was about all they had in common. Snooks is a tall scruffy thirty-something Australian, while Balmond’s is shorter, with a thin white beard highlighting his olive complexion and a shiny bald head also lined with white hair.

As the presentations began it quickly became evident that Balmond deserved his big reputation as a non-conventional designer and teacher. "Make an assumption and jump," he told us as we crowded around him in the studio aisle, but "be careful to reevaluate your assumptions." He was absorbed in our presentations with an attention and curiosity I have rarely seen in other professors. Balmond's interest in the studio was clearly not only to teach, but also to learn. Inquisitive and instructive, his statements imbued us with a confidence to explore this new idea of non-linear design. Balmond seemed to welcome uncertainty: "At the beginning you want to be vulnerable." More like invention than conventional design, the non-linear or non-hierarchical design process provides the uncertainty that he desires with the upside of potentially new, more efficient, interesting and ultimately successful building designs. By exploring new design systems and making bold assumptions, he believes we can discover design and construction processes that we would not find through traditional design methods.

During the four and half hour session Balmond never waned. He moved through the fourteen students—two presentations followed by a discussion--continuing to provide acute direction and inspiration for each of us. With students fading fast (we had been up most of the night working), the presentations ended after eight. We all were looking forward eagerly to some food and much needed sleep when Snooks announced that we should form into working groups of three. These groups were to present a cohesive design statement at ten the next morning. Groups are a common part of studio projects, but forming them can be tricky. As Balmond and Snooks walked out, frantic negotiation ensued.

04 March 2010

Degree NAAB'd?

It looks like the pages of a giant high school yearbook have been ripped out and pasted over the glass surrounding the galleries at school. I assumed the overly posed black-and-white wrapping was part of a fine art project until I realized the National Architectural Accrediting Board, the organization that regulates all architecture schools in the country, was visiting this week.

In something like a tax audit, every three to six years, the board visits the school and does a detail review of all the curriculum, faculty, and student work and confirms whether the school is adequately educating its students to enter the architecture profession. Behind one glass wall covered in smiling students and building models was the NAAB temporary office, and the other, the lower gallery, was the student work for review.

Being one of the most established architecture schools in the country, the review should be a formality--A pat on the back and a few suggestions for improvement. But there have been some rumors surrounding the review--one being the difficult search through the student work to find a floor plan that included toilets and handrails.

Their findings will be announced on Friday at a school wide closing reception. Hopefully our faces will still be smiling.

25 February 2010

If Termites Taught Architecture

Our studio met for the first time last Friday afternoon. The group included fourteen lucky lotto winners (eight Asians, six Americans, and only two females,) and a guy named Roland Snooks, Cecil Balmond’s assistant. Snooks is a scruffy youngish Australian, his black hair is meticulously styled—something like a peacock that just fought off a predator. Kokkugia, the name of his firm in New York, is according to his website " a reference to the desire to build the seemingly impossible," but perhaps more accurately represents the seeming impossibility of building for young firms. Like most architects under forty who teach at PennDesign (and many other architecture schools,) despite his talent and frequent publication, his designs have never been built. He has worked frequently with Balmond’s firm Arup on built projects.

Snooks’ first announcement was that Balmond would not be here for at least a week. His office is in London and it is rumored that he only comes to Penn five or six times a semester to meet with students. I have heard him lecture, but I have never met him personally. Roland's job is to run the studio from day to day. Despite Balmond's frequent absence, I wanted to be in his studio to explore non-linear design.

In the first meeting with Roland we spent six hours trying to define non-linear. While we never came up with an exact definition, it is perhaps the uncertainty of the process that provides its greatest potential over a traditional design method. From what I understand so far, non-linear design is a way of organizing a system without using a step by step process or a predefined hierarchy. Frequently used by nature to create incredibly complex systems, non-linear design imbeds simple repetitive patterns into individual agents whether they are cells or termites. In the case of termites, each insect has the ability to store a few rules that could be understood as “Go search for food”, “Go home” or “Build.” One termite alone would not produce anything significant using these rules, however, when the rules are followed by ten thousand termites, complex order emerges in the form of a ten foot tall mound with hundreds of feet of tunnels. Each termite is independently following the same rules—there is no individual architect to their home, yet the result is a structure that lasts for ten to fifteen years.

These instructions not only account for termite mounds, but also describe the growth of trees, the way-finding of honey bees and at a large scale--the organization of human cities. The beauty of non-linear design is that incredibly complex organisms can emerge from simple rules. The goal of the studio is to explore how, with the right rules, unexpected and successful results will emerge.

Balmond believes in the potential of non-linear design for architecture, despite the lack of precedents. Can you design a non-linear structural system for a building? Can you organize the function of the different rooms in a building non-linearly? I’m not sure, but we are going to try.

And Cecil Balmond is finally coming next week. Maybe.

10 February 2010

Studio Confirmation

A text from my friend Jim let me know that I did get into the Cecil Balmond studio. Having gone home for a nap which will be a rare luxury once studio starts, I hurriedly peddled back to school to confront the other major gamble of the beginning of the semester--claiming a space in the studio. One semester I missed the desk selection process and ended up in the main thoroughfare of the studio. By the end of the semester I had developed a scooting complex--always inching my chair forward so people wouldn't bump into me as they passed. This year our studios are on the third floor where there isn't a desk in the hallway, but there are definitely better seats--away from the doors and the constantly blowing air vents.

I located the Balmond studio on the floor plan on the west side. And in a frenzy of equally selfishly-motivated classmates, I claimed a wall-side spot--the other side being open to the floor below with only a half-wall -- with my back to the door and good friend Jim in proximity.

My final task was getting comfortable. The brand new desks last semester were so terrible that I spent the first week and a half of school modifying mine. The chairs only adjusted from too high to even higher, and the desk shelving bruised my shins at the ankle and knee. Both chair and desk were on wheels, so pulling yourself up to the desk brought both you and the desk half the distance to the other. I added five inches to the height of the desk with aluminum wheel-less legs and replaced the shin-beating steel shelves with a wood foot rest and side shelving, complete with a pencil tray. I didn't want to part with this desk. With a little more help from Jim, we brought the desk from the East side across to the new studio. My move was complete.

I located the Balmond studio on the floor plan on the west side. And in a frenzy of equally selfishly-motivated classmates, I claimed a wall-side spot--the other side being open to the floor below with only a half-wall -- with my back to the door and good friend Jim in proximity.

My final task was getting comfortable. The brand new desks last semester were so terrible that I spent the first week and a half of school modifying mine. The chairs only adjusted from too high to even higher, and the desk shelving bruised my shins at the ankle and knee. Both chair and desk were on wheels, so pulling yourself up to the desk brought both you and the desk half the distance to the other. I added five inches to the height of the desk with aluminum wheel-less legs and replaced the shin-beating steel shelves with a wood foot rest and side shelving, complete with a pencil tray. I didn't want to part with this desk. With a little more help from Jim, we brought the desk from the East side across to the new studio. My move was complete.

09 February 2010

Studio Royale

The lottery--every architecture student’s education boils down to it. It is the architecture department's method for dividing the class into each professor’s studio, and studio is the core of architectural education. The studio you draw shapes your explorations, focuses your interests and influences your thinking about architecture for the extent of your education and career. Today is my final architecture school lottery. And I want Cecil Balmond, a structural engineer.

It's not typical for an engineer to teach a design studio, but this is not a typical structural engineer. The Birds Nest Stadium for the Beijing Olympics and the Seattle Public Library are two better known projects of ARUP where Mr. Balmond is the deputy chairman. In addition to their built work, Balmond opened an office branch called the Advanced Geometry Unit(AGU) that explores new ways of designing building structure using complex geometry and computer programming. Their work forms the basis of his architecture studio at Penn and the reason I want to get his studio in the lottery.

For the lottery, students submit a ranking of all the offered studios, and the administration assigns the groups based on the rankings. In my class there are eight choices. The lottery is a process that I don’t think anyone truly understands, but it is intended to give as many students as possible one of their top three choices rather than giving half the students their first and the other half their fourth choice or lower. My chances for getting Balmond’s studio are about as good as winning from a Pick Four scratch off ticket. Not only is the selection based on making as many people as possible happy, but some students have priority over me because they were selected for the prerequisite class last semester. For me to be selected for the studio, enough of the students with priority have to rank other studios higher, and then I have to be randomly selected from the non-priority students that put Cecil Balmond’s studio first.

The rankings were due at noon, and now I wait. Results will be posted in an hour or two and they are final, no negotiations or alterations.

It's not typical for an engineer to teach a design studio, but this is not a typical structural engineer. The Birds Nest Stadium for the Beijing Olympics and the Seattle Public Library are two better known projects of ARUP where Mr. Balmond is the deputy chairman. In addition to their built work, Balmond opened an office branch called the Advanced Geometry Unit(AGU) that explores new ways of designing building structure using complex geometry and computer programming. Their work forms the basis of his architecture studio at Penn and the reason I want to get his studio in the lottery.

For the lottery, students submit a ranking of all the offered studios, and the administration assigns the groups based on the rankings. In my class there are eight choices. The lottery is a process that I don’t think anyone truly understands, but it is intended to give as many students as possible one of their top three choices rather than giving half the students their first and the other half their fourth choice or lower. My chances for getting Balmond’s studio are about as good as winning from a Pick Four scratch off ticket. Not only is the selection based on making as many people as possible happy, but some students have priority over me because they were selected for the prerequisite class last semester. For me to be selected for the studio, enough of the students with priority have to rank other studios higher, and then I have to be randomly selected from the non-priority students that put Cecil Balmond’s studio first.

The rankings were due at noon, and now I wait. Results will be posted in an hour or two and they are final, no negotiations or alterations.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)